Nipah virus (NiV) is a highly virulent zoonotic pathogen that represents a major public health concern because of its high fatality rate and ability to spread between humans. The virus was first recognized during an outbreak in Malaysia in 1998–1999 and is classified under the Henipavirus genus of the Paramyxoviridae family. Fruit bats of the Pteropus genus serve as the natural reservoir, and human infection can occur through direct contact with bats, via intermediate animal hosts such as pigs, or through close contact with infected persons.

Clinically, Nipah virus infection demonstrates a broad spectrum of manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe respiratory disease and lethal encephalitis. Reported case fatality rates vary from 40% to 75%, depending on the outbreak and the level of healthcare support available. Repeated outbreaks in South and Southeast Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh, underscore the virus’s significant epidemic potential.

We'll discus the topic under the epidemiological triad [Agent, Host, Environment], Transmission, its Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention.

Join Weekly Health Newsletter

Every week, I will share with you information about Natural Health, Diet, Exercise, Yoga & Wellness.

AGENT FACTOR

Nipah virus (NiV) belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family and is classified under the Henipavirus genus. Owing to its high virulence, significant mortality rate, and the lack of an effective antiviral therapy or licensed vaccine, NiV is designated as a Biosafety Level-4 (BSL-4) pathogen.

Structure

Although NiV shares similarities with other paramyxoviruses, it exhibits certain distinct structural features.

- Presence of reticular cytoplasmic inclusions located near the endoplasmic reticulum

- Comparatively larger virion size.

Such ultrastructural differences help distinguish NiV from classical paramyxoviruses, despite overall structural resemblance.

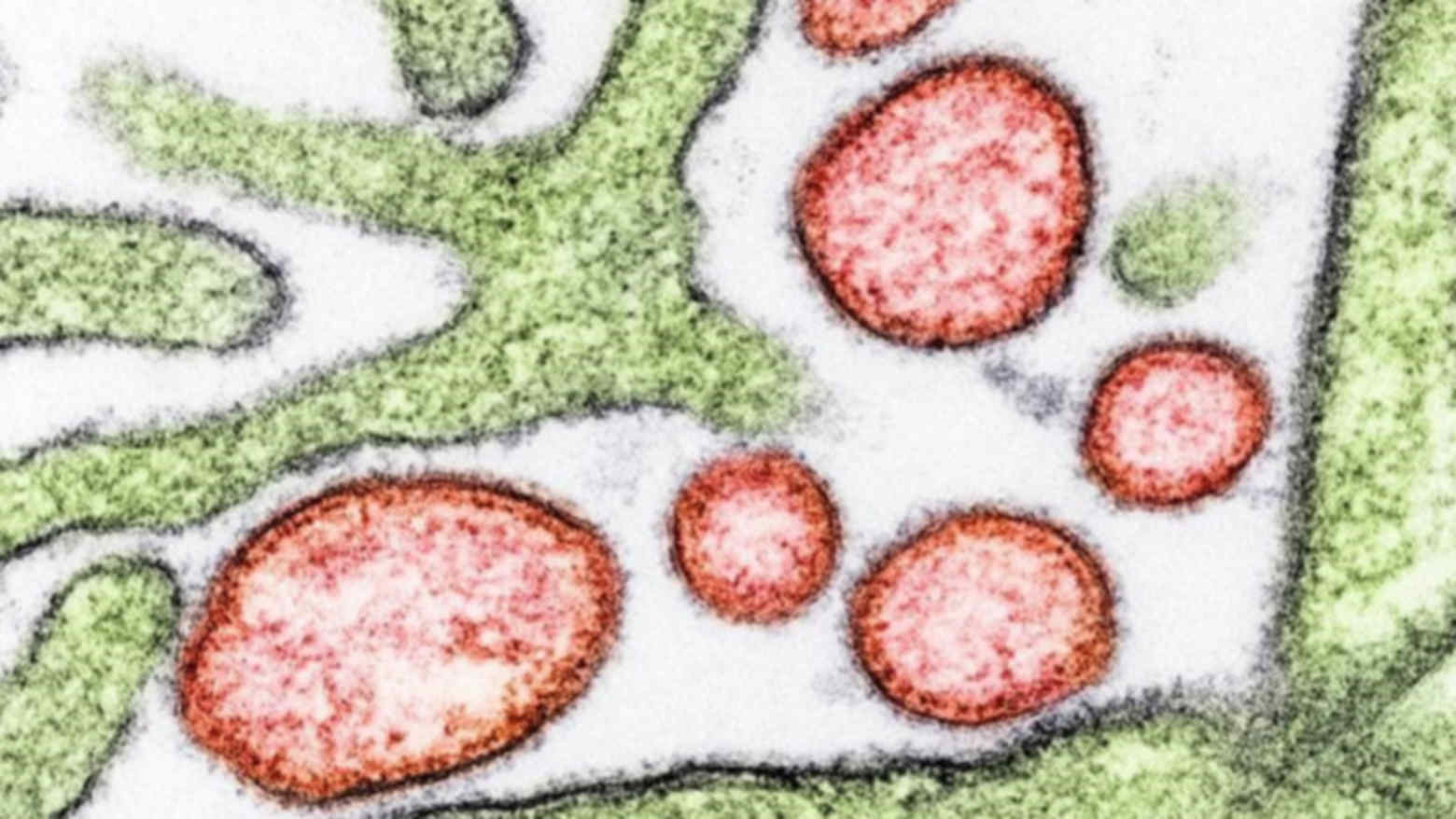

Nipah Virus under Microscope

Genome Organization

Nipah virus is a negative-sense, single-stranded, non-segmented, enveloped RNA virus exhibiting helical symmetry. The viral genome is approximately 18.2 kilobases in length and consists of six genes arranged in a 3′–5′ orientation.

These genes encode essential viral proteins : Nucleocapsid protein, Phosphoprotein, Matrix protein, Fusion glycoprotein, Attachment glycoprotein, and the Large polymerase protein.

- The nucleocapsid protein, phosphoprotein, and large polymerase protein together form the viral ribonucleoprotein complex, which is essential for viral replication and transcription.

- The matrix protein plays a crucial role in viral assembly and budding, linking the ribonucleoprotein core to the viral envelope.

Mechanism of Viral Entry

- Viral entry into host cells is mediated by two surface glycoproteins: the attachment glycoprotein and the fusion glycoprotein.

- The attachment glycoprotein binds to specific host cell receptors, initiating viral entry.

- This interaction triggers activation of the fusion glycoprotein, which undergoes cleavage into two subunits, F1 and F2.

- The F1 subunit is primarily responsible for mediating the fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, allowing entry of the viral genome into the cell.

Role of Epherin Receptor

Research has shown that binding of the host cell receptor ephrin-B2 to the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein induces allosteric conformational changes. These changes activate the fusion glycoprotein and facilitate receptor-dependent viral entry into host cells, particularly in endothelial and neuronal tissues.

HOST FACTORS

Host factors play a crucial role in determining susceptibility, disease severity, and transmission dynamics of Nipah virus (NiV) infection.

Fruit Bats

Natural Reservoir

Fruit bats of the Pteropus genus serve as the natural reservoir of Nipah virus. Infected bats remain largely asymptomatic while shedding the virus in saliva, urine, feces, and partially eaten fruits. Their ability to fly long distances and their close proximity to human habitats facilitate viral spillover events.

Intermediate Animal Hosts

Certain domestic animals can act as intermediate hosts, amplifying viral transmission. Pigs played a major role during the initial outbreak in Malaysia, where close contact between infected pigs and humans led to widespread transmission. Other animals, such as horses and goats, have also been found to be susceptible, although their role in large-scale outbreaks remains limited.

Human Host

Humans are accidental hosts of Nipah virus infection. Factors such as close contact with infected animals, consumption of contaminated food products, and exposure to infected individuals increase the risk of infection. Healthcare workers and family caregivers are particularly vulnerable due to prolonged and close exposure to infected patients.

Nipah virus exhibits a strong affinity for ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 receptors present on host cells. These receptors are highly expressed on endothelial cells, neurons, and respiratory epithelium, explaining the virus’s predilection for the nervous system and lungs. Binding of the viral attachment glycoprotein to these receptors facilitates viral entry and cell-to-cell spread.

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against Nipah virus infection. However, NiV has developed mechanisms to evade host immunity, particularly by inhibiting interferon signaling pathways. Impaired early immune responses contribute to high viral replication and severe disease.

Disease severity is influenced by host-related factors such as age, nutritional status, comorbidities, and immune competence. Delayed healthcare access and inadequate supportive care further exacerbate disease outcomes. Host genetic factors may also play a role, although these are not yet fully understood.

Human to Human Transmission

Host behaviours significantly affect transmission. Practices such as inadequate infection control, lack of personal protective equipment, and close physical contact with infected individuals increase the risk of secondary transmission. Cultural practices involving caregiving and burial rituals may also contribute to virus spread during outbreaks.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Environmental factors play a critical role in the emergence, transmission, and recurrence of Nipah virus outbreaks. These factors influence bat ecology, human–animal interactions, and opportunities for viral spillover.

Habitat Loss and Deforestation

Deforestation and large-scale land-use changes disrupt the natural habitats of fruit bats (Pteropus species), forcing them to migrate closer to human settlements. Loss of forest cover reduces natural food sources for bats, increasing their reliance on cultivated fruits and agricultural areas, thereby enhancing the risk of viral transmission to humans and domestic animals.

Urbanisation and Agricultural Expansion

Rapid urbanization and expansion of agricultural activities bring humans, livestock, and wildlife into closer contact.

Deforestation and Habitat Loss

Orchards and farms established near bat roosting sites facilitate contamination of fruits, animal feed, and water sources with bat saliva, urine, or feces, creating conditions favorable for Nipah virus spillover.

Climate and Seasons

Seasonal variations significantly influence Nipah virus transmission. In South Asia, outbreaks commonly occur during winter months, coinciding with increased consumption of raw date palm sap. Climatic factors such as temperature changes, rainfall patterns, and drought affect bat feeding behavior, viral shedding, and human exposure risks.

Date Pal Sap Collection

Food Contamination Practices

Traditional food-harvesting and storage practices contribute to environmental exposure. Collection of raw date palm sap in open containers allows contamination by bats, serving as a major route of Nipah virus transmission in Bangladesh and parts of India.

Similarly, consumption of partially eaten fruits discarded by bats increases infection risk.

Livestock and Animal Housing

Poor livestock housing conditions, particularly pig farming near fruit trees or bat habitats, increase the risk of animal infection and viral amplification. Environmental contamination of animal feed and water sources can facilitate rapid spread among livestock, which may then transmit the virus to humans.

PATHOGENESIS

Viral Entry into Host

Infection begins when Nipah virus enters the human body through the respiratory tract, oral mucosa, or gastrointestinal tract. The viral attachment glycoprotein binds to host cell receptors, primarily ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3, which are abundantly expressed on endothelial cells, neurons, and respiratory epithelial cells.

This receptor binding triggers activation of the viral fusion glycoprotein, allowing fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane and entry of the viral genome into the cell.

Primary Replication

Following entry, the virus undergoes primary replication at the site of entry, particularly in respiratory epithelial cells. The viral ribonucleoprotein complex initiates transcription and replication of viral RNA in the host cell cytoplasm, leading to production of new virions.

Viremia and Dissemination

Pathogenesis of Nipah Virus Infection

After initial replication, Nipah virus spreads through the bloodstream, resulting in viremia. The virus disseminates to multiple organs, including the lungs, central nervous system, spleen, kidneys, and heart. Endothelial cells serve as major targets, facilitating widespread vascular involvement.

Endothelial Infection and Vasculitis

A hallmark of Nipah virus pathogenesis is infection of vascular endothelial cells, leading to endothelial dysfunction and systemic vasculitis. Viral replication in endothelial cells causes inflammation, thrombosis, increased vascular permeability, and microinfarctions. These vascular changes contribute significantly to tissue ischemia and organ damage.

Neuroinvasion

Nipah virus demonstrates marked neurotropism. The virus gains access to the central nervous system either through hematogenous spread across the blood–brain barrier or via infected endothelial cells. Once in the brain, viral replication leads to neuronal damage, inflammation, and necrosis, resulting in acute encephalitis, seizures, altered consciousness, and coma.

Respiratory System Involvement

Infection of respiratory epithelium and pulmonary endothelium leads to acute respiratory distress characterized by cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia. Extensive alveolar damage and pulmonary edema may occur, contributing to high mortality and increased risk of human-to-human transmission via respiratory secretions.

Immunopathology

Nipah virus has evolved mechanisms to suppress the host innate immune response, particularly by inhibiting interferon signaling pathways. This immune evasion allows uncontrolled viral replication and delays effective antiviral responses, contributing to disease severity.

Excessive immune activation in later stages may lead to cytokine release and inflammatory tissue damage. The combined effects of direct viral cytotoxicity and immune-mediated injury exacerbate organ dysfunction.

Unique Feature

A unique feature of Nipah virus infection is the occurrence of relapsing or late-onset encephalitis weeks to months after apparent recovery. This is believed to result from persistent viral infection or reactivation within the central nervous system.

MODES OF TRANSMISSION

Bat-To-Human, Animal-To-Human, Human-To-Human Transmission

Bat-To-Human

Fruit bats (Pteropus species), the natural reservoir of Nipah virus, transmit the virus to humans through contamination of food or water with their saliva, urine, or feces. Consumption of raw or partially processed date palm sap contaminated by bats is a well-documented route of transmission. Eating fruits partially eaten or contaminated by bats also increases the risk of infection.

Animal-To-Human

Domestic animals, particularly pigs, can act as intermediate hosts and amplify the virus. Humans may become infected through close contact with infected animals, their respiratory secretions, blood, or tissues. This mode of transmission was prominent during the initial outbreaks in Malaysia among pig farmers and slaughterhouse workers.

Human-To-Human

Person-to-person transmission has been documented in several outbreaks, especially in healthcare and household settings. Transmission occurs through close contact with infected individuals, exposure to respiratory droplets, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces.

Transmission

Caregivers and healthcare workers are at increased risk in the absence of adequate infection control measures.

Nosocomial

Hospital-based transmission occurs when appropriate infection prevention and control practices are not followed. Aerosol-generating procedures, improper use of personal protective equipment, and inadequate isolation facilities contribute to nosocomial spread.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The incubation period typically ranges from 5 to 14 days, but in some cases may extend up to 45 days.

Some individuals may remain asymptomatic or develop only mild illness. However, even mild cases may progress rapidly to severe disease.

Prodromal Symptoms

Initial symptoms are non-specific and may resemble common viral illnesses, including : Fever, Headache, Myalgia, Fatigue, Sore throat, Nausea and vomiting.

Respiratory Symptoms

Respiratory involvement is common and may be mild or severe. Features include:

- Cough, Shortness of breath,

- Chest discomfort

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in severe cases

Respiratory symptoms increase the risk of human-to-human transmission.

Neurological Involvement

Neurological involvement is a hallmark of Nipah virus infection and often indicates severe disease. Features include:

- Altered sensorium

- Drowsiness or confusion

- Seizures

- Focal neurological deficits

- Acute encephalitis leading to coma

Other Symptoms

Systemic involvement may result from widespread vasculitis and endothelial damage, leading to:

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Multiorgan dysfunction

A distinctive feature of Nipah virus infection is relapsing or late-onset encephalitis, occurring weeks to months after apparent recovery. Symptoms include behavioral changes, seizures, and neurological deterioration.

Complications

- Severe encephalitis

- Respiratory failure

- Multiorgan failure

- Death [Case Fatality Rate is 40-75%]

DIAGNOSIS

Early and accurate diagnosis of Nipah virus infection is essential for patient management and outbreak control. Due to the high infectivity of the virus, diagnostic testing is performed in specialized high-containment laboratories.

Specimen

- Blood (serum, plasma)

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- Throat and nasal swabs

- Urine

- Respiratory secretions

RNA Detection

Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) is the gold standard for early diagnosis. It detects Nipah virus RNA in clinical specimens and is highly sensitive and specific. RT-PCR is most useful during the acute phase of infection.

Serology

Serological assays are used to detect antibodies against Nipah virus:

- IgM antibodies - recent or acute infection

- IgG antibodies - past exposure or recovery

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is commonly used for antibody detection.

Nipah Virus (VERO NR596 Cells) Malaysia Strain

Virus Isolation

Virus isolation can be performed in cell culture but is restricted to Biosafety Level-4 (BSL-4) laboratories due to the high risk involved. This method is primarily used for research and confirmatory purposes rather than routine diagnosis.

Imaging

Although not confirmatory, imaging studies support diagnosis:

- MRI brain may show multiple small hyperintense lesions suggestive of encephalitis

- Chest X-ray / CT scan may reveal pulmonary infiltrates or ARDS

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of tissue samples can detect viral antigens in affected organs, particularly in fatal cases. This method helps in post-mortem diagnosis and pathological studies.

Differential Diagnosis

- Japanese encephalitis,

- Herpes simplex encephalitis,

- Dengue,

- Leptospirosis, and

- COVID-19.

MANAGEMENT

Currently, there is no specific antiviral therapy or licensed vaccine available for Nipah virus infection. Management is largely supportive, with emphasis on early diagnosis, intensive care, and strict infection control measures.

Symptomatic Treatment

- Management of fever and pain

- Adequate hydration and electrolyte balance

- Nutritional support

- Patients with severe disease require admission to intensive care units.

- Respiratory Support :

- Respiratory complications are common and may progress rapidly. Management includes:

- Oxygen therapy

- Non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation in cases of respiratory failure

- Management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Neurological Management :

- Patients with encephalitis require careful neurological monitoring. Management includes:

- Control of seizures using antiepileptic drugs

- Measures to reduce raised intracranial pressure

- Maintenance of airway protection in unconscious patients

Drugs under Study

Drug Name | Effect in Humans | Effect in Animals | In-Vitro Test |

|---|---|---|---|

Ribavirin | In Malaysia outbreak during 1998/1999, a 36% reduction in mortality. | No effect in animals | - |

Remdesivir (GS-5734; Veklury®) | Not tested in humans | Shows 100% survival rate in AGM model against NiV-B | - |

Favipiravir (T-705; Avigan®) | Not tested in humans | Full protection against NiV- M | - |

Griffithsin (GRFT) | Not tested in humans | In syrian hamster model against NiV-B shows 15% and 35% survival rate. | - |

4’ azidocytidine (R1479) | Not tested in humans | Not tested in animals | Shows activity against NiV, but its prodrug is inactive; therefore withdrawn from clinical trials |

4′-chloromethyl-2′-deoxy-2′-fluorocytidine (ALS-8112) | Phase I and II of clinical trials against respiratory syncytial virus infection | Not tested in animals | Strong effect against NiV in vitro at low micromolar range. |

Lipopeptide fusion inhibitors | 50% survival rate in Syrian golden hamster’s model. In AGMs model shows 33% survival rate. | - | - |

PREVENTATIVE MEASURES

Prevention of Bat-to-Human Transmission

- Avoid consumption of raw or unprocessed date palm sap.

- Use physical barriers (such as bamboo skirts or covers) to prevent bats from accessing sap collection pots.

- Wash and peel fruits thoroughly before consumption.

- Avoid eating fruits that appear partially eaten or contaminated by bats.

Prevention of Animal-to-Human Transmission

- Maintain proper animal housing away from fruit trees and bat habitats.

- Implement biosecurity measures in livestock farms, especially pig farms.

- Use protective gloves and clothing when handling sick animals.

- Promptly isolate and report illness in domestic animals.

Prevention of Human-to-Human Transmission

- Early identification and isolation of suspected and confirmed cases.

- Use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by healthcare workers and caregivers.

- Avoid direct contact with body fluids of infected individuals.

- Safe burial practices with minimal handling of the deceased.

Infection Control in Healthcare Settings

- Adherence to standard, contact, and droplet precautions.

- Use of N95 masks during aerosol-generating procedures.

- Proper disinfection of hospital equipment and patient environments.

- Training healthcare workers in infection prevention and control practices.

Public Health Measures

- Strengthening surveillance systems for early outbreak detection.

- Rapid contact tracing and monitoring of exposed individuals.

- Quarantine of high-risk contacts when necessary.

- Timely risk communication and public awareness campaigns.

Vaccination

Vaccine Name | Country | Phase of Trial |

|---|---|---|

ChAdOx1 | United States (Oxford) | Phase 2 |

PHV02 | United States | Phase 1 |

mRNA-1215 | United States | Phase 1 |

HeV-sG-V | USA | Phase 1 |

CD40.NiV | Vaccine Research Institute of the ANRS MIE/Inserm | - |

SITUATION IN INDIA

Scroll.in

In West Bengal (North 24 Parganas district), two laboratory-confirmed cases of Nipah virus infection were reported in late December 2025 and confirmed in January 2026. Both patients are young healthcare workers (nurses) from the same private hospital.

One patient has shown clinical improvement while the other remained critically ill as of the latest reports.

Over ~190 contacts (including health workers and community contacts) were identified and tested; none have tested positive or shown symptoms.

The World Health Organization said that the risk posed by the Nipah virus was “moderate at the sub-national level, and low at the national, the regional and global levels”. The World Health Organization said it assessed the risk from Nipah to be “moderate” at the sub-national level as no specific drugs or vaccines against it are available, and because early diagnosis is difficult.

0 comments